Salomon Kashtan

Salomon Kashtan (1781–1829) was an Eastern European chazzan, composer, and itinerant performer, widely regarded in later cantorial literature as a foundational figure in the development of nineteenth-century Lithuanian and Volhynian cantorial style. He served as chazzan of the community of Dubno (today in western Ukraine), though he spent much of his career travelling and performing throughout Eastern and Central Europe. Kashtan crossed political borders repeatedly, performing both within and outside the Russian Empire at a time when such movement was neither simple nor common.

Kashtan was noted by contemporaries and later scholars for an unusually powerful tenor voice, extreme virtuosity in coloratura, and an ability to elicit intense emotional responses from congregations. He is among the earliest synagogue cantors whose musical repertory survives in written form, preserved primarily through the efforts of his son, Hirsch Weintraub, who also authored a detailed biography of him in the nineteenth century.

Early life and training

Kashtan was born in Alt-Kostantin in the region of Volhynia, about 175 miles west of Kiev. His father, Shimshon was the baal koreh of Alt-Kostantin and is described as being an extremely pious man. The name Kashtan (chestnut) originated as a nickname, reportedly referring to Salomon's reddish-brown hair, and was later applied to members of his immediate family. Modern secondary literature often treats the names Kashtan and Weintraub interchangeably, though hereditary surnames were not consistently used among Jews in the Russian Empire at the time of his birth. Kashtan was apprenticed at the age of nine to Kalman the lame, the cantor of Mohilev, and and spent much of his youth travelling and learning his craft.

Career and travels

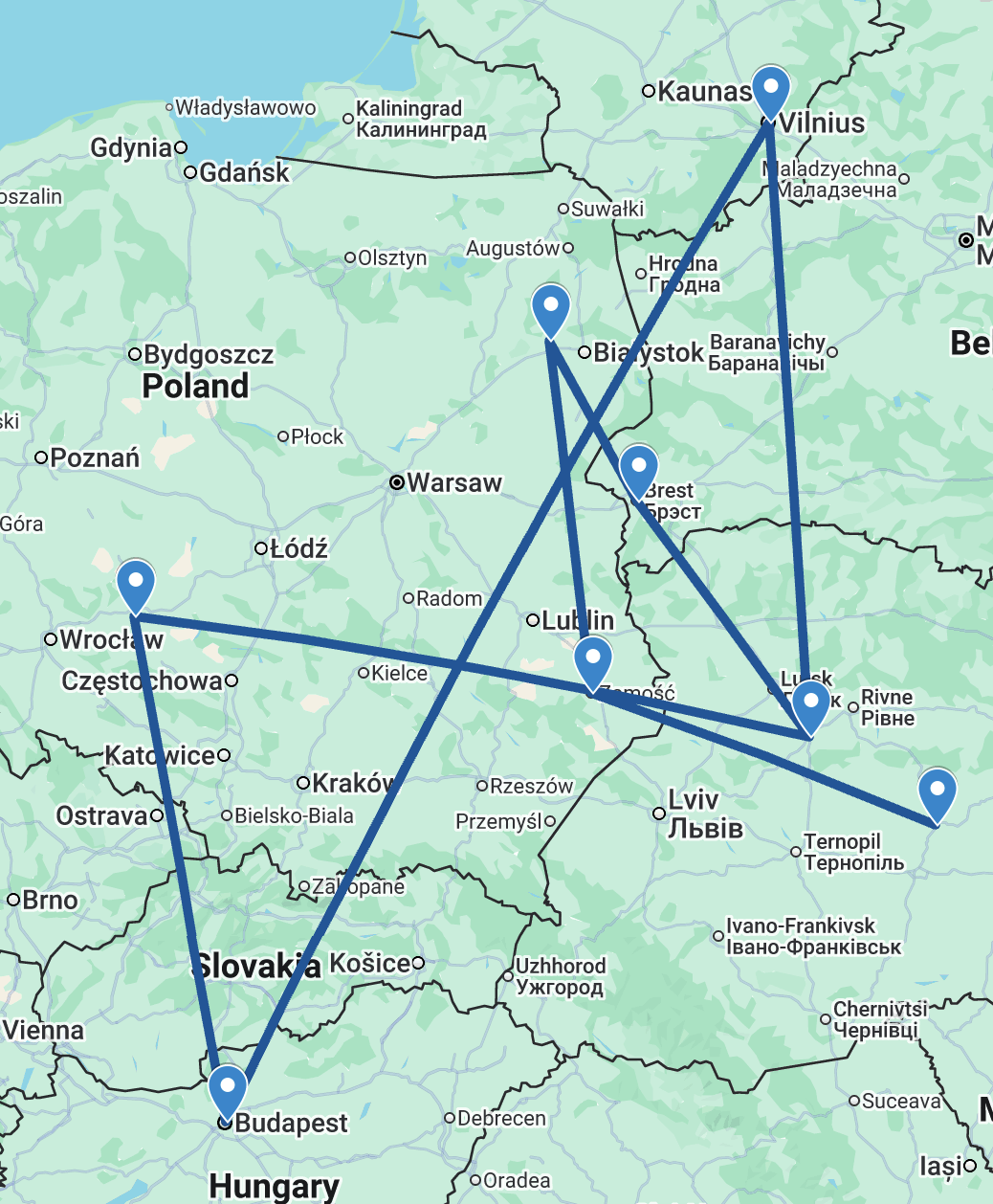

Map of Salomon Kashtan's permanent positions.

Kashtan became known for an unusually powerful tenor voice and virtuosic coloratura. He began organizing his own choir singers, (including his younger brother, Nochum Leib as a bass) and was an immediate success wherever he went, first in Zamoshtsh, where he stayed for only a year. His next position was in Tiktin where he stayed for three years before searching for greener pastures. Next he accepted a call from Brisk where he stayed for six years, though even during this period he continued roaming to both nearby towns and faraway regions, often for months at a time.

Following his tenure in Brisk, he took on the position of chazzan in Dubno for which he held a lifetime association. Around this time, he made guest appearances in Riga, Odessa amd Vilna each of them for months at a time, and with resounding success, returning to Dubno only for the high holidays. Dubno was not a large city and the synagogue repeatedly struggled to meet their financial obligations to their cantor. After constant frustration, Kashtan decided to leave the congregation and officiate in Lemberg for the high holidays.

Surprisingly, Kashtan then headed westwards, where he again triumphed despite more of an overt stylistic difference between the Western and Eastern Ashkenazic service. His first stops were in Kempen, Breslau, Lissa and Posen. The shabbat he officiated in Kempen left such a huge impression on the congregants that they asked him to accept a permanent position, which Kashtan eventually agreed to, staying for about a year.

Then he set his sights on Hungary which he had hitherto not yet explored. His fame preceded him in Alt-Ofen and they immediately offered him a permanent position. He been there scarcely a short time when the community of Vilna remembering his appearance from a few years prior wrote asking him to return there as permanent chazzan, which he also accepted.

Court action and return to Dubno

However, during these travels the congregation of Dubno still held a deep devotion to their former chazzan, and now that he was back in the same country, they instituted a court action whilst simultaneously attempting to sway Kashtan with a promised salary hike. The suit dragged on for several years, during which Kashtan officiated in Vilna without being able to sign a permanent contract. Eventually Rabbi Ephraim Zalman Margulies pronounced that Kashtan should return to Dubno. The Vilna community appointed Tzvi Hirsch Bochur (father of Yoel David Loewenstein) as their next chazzan.

Kashtan decided to settle down and enjoy some serenity in Dubno. However this plan was short-lived when a businessman who he had invested his savings with declared bankruptcy. A new tour was mapped out to help him recoup his losses, across many cities in the Russian empire.

Kashtan died in 1829, following a period of serious illness. His death was widely lamented in later cantorial literature, as the premature loss of a defining musical figure. Sources note that both he and his brother died in the same month.

Style and influence

Kashtan is credited with establishing a distinctive school of Eastern chazzanut centered on Volhynia. His style, rooted in the Ahavah Rabbah mode, was associated with depth and dignity, and stood in contrast to the more lyrical, ornate approach later popularized in Odessa by Betzalel Shulsinger.

Kashtan’s vocal art was frequently described as overwhelming in emotional effect. Contemporary descriptions emphasize the precision and speed of his coloratura and the intensity with which he delivered penitential texts. He was also known for maintaining traditional devotional character even while using elaborate musical ornamentation, an approach that influenced later Eastern European cantorial practice. Writers in the 19th and early 20th centuries referred to him as the greatest cantor of his era, and later comparisons likened his stardom to that of Yossele Rosenblatt a century later.

Pupils and legacy

Kashtan is frequently described in nineteenth and twentieth-century cantorial writing as a foundational figure in Lithuanian cantorial tradition, and one of the earliest cantors whose art achieved pan-regional fame without the aid of print media or modern technology.

Among his best‑known pupils were his brother Nochum Leib, a cantor in Berditchev, and his son Hirsch Weintraub, who succeeded him in Dubno and later brought elements of Kashtan’s tradition to Central Europe. Weintraub later reworked some of Kashtan’s melodies into a more Europeanized choral idiom while preserving the older Eastern style in other compositions. Accounts of Kashtan’s school stress its lasting impact, noting that his melodies and manner of delivery were widely imitated across the 19th century.

Weintraub published a collection of Kashtan’s music in 1859 and later wrote a biography of his father serialized in Hamaggid in 1875. These efforts make Kashtan one of the first Eastern European chazzanim whose music and life were preserved in print. Nevertheless Weintraub's comment in the preface to his work suggests that his father's compositions were out of vogue in Western Europe in the decades after his passing: "They should be considered rather as antiquities. I have transcribed them for those Jewish cantors who are trained in and are familiar with the ancient spirit, with coloratura and embellishment, as they are especially tolerated and demanded in Oriental song."